我們都很無奈,不知道該如何面對未來的挑戰,自從88風災,我們被強迫撤離原鄉部落之後,生活在安置中心到設置在瑪家農埸的永久屋,總是有太多迷惘,也一直沒有辦法適應,住在永久屋又沒有土地,要作什麼?在原鄉的米糧很多,而且山上的風很香。

We all feel helpless, clueless as to how to face the challenges ahead. Ever since the devastation of Typhoon Morakot that led to forced evacuation from our native tribes, we have been at a loss, unable to adapt to our relocated life in the resettlement centres and the permanent housing estates on the Makazayazaya Farm. What uses does it have to live in permanent housing without any lands? Our ancestral lands abound in rice, and the mountain winds are imbued with fragrance.

一位部落耆老在2009年莫拉克風災之後,述說了她內心的無奈和對原鄉的追憶和感受

A village elder, after Typhoon Morakot hit in 2009, expressing her deep misgivings and recalling fond memories and sentiments for her native lands

「山上的風很香」主要是想藉著影像紀錄,紀錄在災後仍然繼續呼吸的族人,因莫拉克風災,造成屏東縣三地門鄉達瓦蘭(大社)部落族人數百年所面對的生活挑戰,諸多的新生活適應,經歷部落的大遷徙,從山上的原鄉跨越隘遼溪至瑪家農場所謂的永久屋,在生活空間與環境改變的過程,部落族人們都真實的面對離鄉背井、生活適應以及心靈重建的課題。莫拉克風災後達瓦蘭部落族人面臨生活適應、遷徙、失根、沒有了土地等疑慮和無奈,又自風災後,在安置所和入住永久屋後,幾乎每個月都有族人過世,因而有部落耆老表示「因為我們的靈魂都在山上,所以我們還是要回歸原鄉。」這句話道出,耆老對原鄉的不捨與留戀。「山上的風很香」希望傳承原住民族人特有的生命韌性與樂觀精神,將數百年來面對災難和遷徙時,透過耆老的話語、眼神和生活價值,感受家園應有的靈魂和重建新家園的夢想和力量。

“Fragrant are the mountain winds” employs images to document the lives of the tribespeople who survived the disaster. The havoc wreaked by Typhoon Morakot posed the greatest challenge in centuries upon the Tavadran (Dashe) tribe in Sandimen Township, Pingtung County. Having endured a long migration from their ancestral lands in the mountains, across Ailiao River, to the so-called permanent housing on the Makazayazaya Farm, the indigenous communities struggle to adapt to their new life in resettlement. They learn to cope with displacement, adjustment, and the reconstruction of their souls and spirits amidst changes in their living space and surrounding environment. Since Typhoon Morakot struck, the people of the Tavadran tribe have been confronted with a deep sense of unease and resignation triggered by migration, adjustment, and the loss of roots and lands. After they relocated to resettlement camps and permanent housing, someone in the tribe passed away almost every month. Some tribal elders explained, “our spirits reside in the mountains, so we have to return to the ancestral lands”, expressing their profound attachment to and nostalgia for their montane native lands. “Fragrant are the mountain winds” strives to pass on the unique resilience and optimism of the indigenous peoples in the face of disasters and migration over the centuries. Through the eyes, words, and wisdom of the elders, it seeks to manifest the soul and spirit of their homeland, while conveying their strength and dreams of rebuilding a new home.

Description of the artwork “Fragrant are the mountain winds” by the artist Etan Pavavalung

“Whatever your eye can see, it’s vecik.”

This line resonated with me while I was conducting my fieldwork in Taiwan with the indigenous Paiwan village known as Paridrayan. Good friend and prolific artist, Etan Pavavalung, once mentioned to me this Paiwan concept known as vecik. The concept, briefly speaking, implies an interconnectedness that links all tangible things with each other. From humans, rocks, and trees to winds and words, they are connected to each other through vecik. It is usually described as lines and/or patterns that can be found on all ‘materials’ such as fingerprints, tree rings, etc.

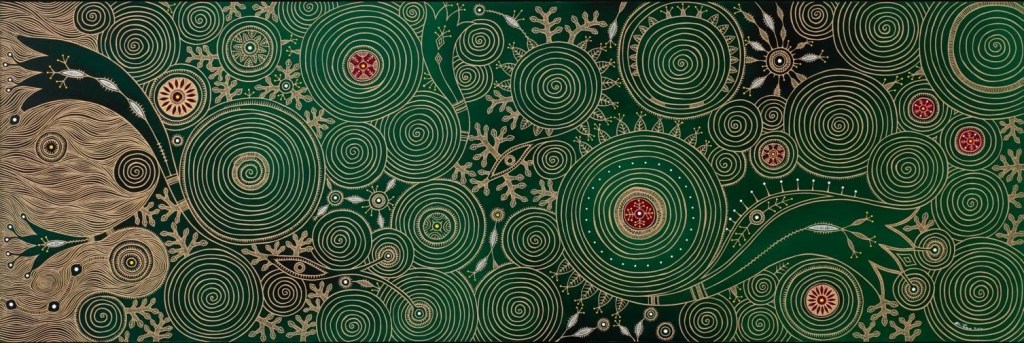

Etan applies this concept to his art practice, creating concentric circles and lines representing vecik often carved or engraved into his works, though what makes his practice unique is his subject matter. Etan produces scenes, narratives, and events of Paiwan myths (mirimiringan), as well as real-life events and stories (tjautsiker). These narratives in themselves do not qualify as vecik because of their non-visual nature. However, when it is made visible, the stories come to life vis-à-vis the vecik connection in his addition of concentric lines. His work “Fragrant are the mountain winds” encompasses scenes from nature with their own unique symbolic qualities. Aiming to portray intangible sensuous phenomena like scent and wind, he employs lines that are carved and drawn onto the canvas – these are vecik lines that make the invisible, visible.

Planning to apply the concept to my thesis, I asked Etan whether music and sound can somehow showcase vecik through a similar application. Etan replied that it would be difficult to apply vecik to music due to its apparent ephemerality. “However,” he added, “something like poetry can be vecik.” He continued, “let’s take for example, a village elder reciting a poem about his childhood. He recites verses about his flower garden from his childhood home as well as reminiscing his childhood days. These words become vecik.” What I understood from this statement is that the site-specificity of the words being uttered, becomes visual. In other words, if you can visualise something through semantic means, it becomes vecik. Perhaps due to its non-fictive elements, one can tell that these memories take place in a tangible and terrestrial context.

Manifesting vecik with squiggly lines

The idea of “poetry” as being something that could allow vecik to weave through had me reflect on academic writing. If we allow ourselves to think about a thesis or article as a kind of long-form prose, is there an element of vecik that is present? After all, I am writing about a physical memory, informed by multiple interactions, interviews, and engagements that usually occur sonically over a period of a year (everyday conversations, digital recordings, jamming with musicians). An academic paper in its printed or digital form, then, renders these observations tangible – “one that the eye can see”. Therefore, these squiggly lines (text) and images, as poetry, allow for the manifestation of vecik.

My PhD topic explores the sonic dimensions of a village, looking at how place is negotiated with sound. I focus on Paiwan soundscapes, investigating the shifting functions and efficacy these sounds represent from the past to today. The tangible memories of my interlocutors are translated into words, albeit shifting between three languages, Paiwan, Mandarin, and English. What I hear and experience is then transcribed into a Word document. I hold a responsibility to my interlocutors – maintaining a sense of earnestness, truthfulness while interpreting/translating their words as faithfully as possible. If this isn’t creative writing, I don’t know what is (of course, keeping in mind the restrictions and specificities of academic writing).

“What is your contribution to knowledge?”, we often get asked. Yet, another way to interpret the question is, to whose knowledge am I contributing to? I believe there are two answers to this. The first and most obvious answer would be to the general academic research community. The ones far detached from your research, from different worlds and research trajectories. The second answer, is also predictably, to our field site and interlocutors. I am not the first researcher to conduct an ethnographic study on the village, nor am I even part of the community. What I contribute to them is an acknowledgement of the vecik connections that bind myself, my (written) words with their voice, music and cosmology. By positioning myself as a poet, I am creating a conglomeration of my interlocutors’ (and my own) thoughts, feelings, memories and being. I write through three languages (maybe four, if you count academic parlance!) in the hope that their voices are made manifest through my squiggly lines, in which vecik weaves through.

Cosmo-ethnography and collectivity

In a 2018 article written by Anand Pandian, he discusses the role of open access journals while reflecting on ethnographic writing. Using a Twitter hashtag as an example, he provides a description of the generative capacities of such a platform where multiple voices come together as “connective tissues” that form an “ecology of knowledge”.

A decolonisation of academic writing that engages the written word is necessary in engaging with such an “ecology of knowledge”. What this means for myself as a researcher, is to take a step back and to revisit my position in the field sans the institutional lens of academia. What does my data become once I successfully put down in words, the plethora of voices that had led to my thesis? Given that vecik is something tangible, do the lines and contours of the written word add on to it? If so, each word acts like a “connective tissue” that becomes part of this ecology of knowledge that expands outward.

As what I call a “cosmo-ethnography”, vecik transcends my position in the field, blurring and perhaps diverging from simple participant observation. It moves beyond ethnography and into cosmology. I am embodying this concept and its place of origin when I say that the act of writing is, in fact, akin to reciting a poem. My attempt at churning out a written document from my experience (based on other embodied experiences), is parallel to that hypothetical village elder who reminisces about a time that he returns to, over and over again, refreshing and revisiting, just with the power of utterance. The voice therefore transports memory (visual, sonic, or otherwise) into a realm of a collective sense of belonging that vecik passes through into the present moment of the poet’s oration. The vecik moves as these moments are formed and/or revisited.

I wonder if, as anthropologists, we could think of our writings as existing beyond the academic canon and instead, be part of an infinite tapestry of knowledge[s]? Why then, should we treat our written research as an accumulation of a memory/experience, which signifies an ending to something that isn’t static? Instead of thinking along the lines of our writings being PDF files in a university’s depository, why shouldn’t we think of our academic writing as a single yet crucial piece of an ever-expanding puzzle we call culture?

Further reading: poem by the artist Etan Pavavalung

這些景 這些事

印記在風災肆虐的地土上

我想要上山

讓心靈隨風走往

傾聽靈魂心旋樂音的居所

在溪水詠讚的大地間

我要重新披上

哼唱原味氣息的風彩衣

那些景 那些事

紀錄著遷徙心靈的 愁與戀

我要再上山

因為心底彷彿聽見

熟黃飄搖山間的米穗聲

在靈鳥相伴的樂音中

站在創傷的山林獵場間

揮別災難的痛和憶

在夢境中切記

山上的風 依舊香

These scenes, these things

On the typhoon-ravaged soil they left imprints

I yearn to go back to the mountains

My heart travels with the winds

To where the music of spirits lingers

Upon the earth where streams sing

To again be donned

By the colourful humming winds

Those scenes, those things

Record the sorrow and love of a migrating soul

I yearn to go back to the mountains

From the bottom of my heart I hear the rustlings

Of ripe rice grains billowing in the winds

In the music accompanied by spirit birds,

Standing in the wounded forest hunting grounds,

I wave farewell to the painful memories of the disaster

While holding dear in my dreams that

Fragrant still, are the mountain winds

Further reading on decolonisation in fieldwork

Mignolo, W.D. 2009, “Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and Decolonial Freedom“, Theory, culture & society, vol. 26, no. 7-8, pp. 159-181.

Stanton, B. 2018, “Musicking in the Borders toward Decolonizing Methodologies“, Philosophy of music education review, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 4-23.

Sium, Desai, and Ritskes 2012, “Towards the ‘tangible unknown’: Decolonization and the Indigenous future”

Parreñas, J.S. 2020, “6. From Decolonial Indigenous Knowledges to Vernacular Ideas in Southeast Asia“, History and theory, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 413-420.

[Image of the village and path in the mountains taken by Jarrod Sim]

[Description of the artwork and the poem translated by Clair Zhang]